In less than a month my semester at UNIS will come to an end. But I certainly will return. The picture above shows me standing in room one of the barrack – the place where I have been spending a lot of time to tend to our plants, such as our approximately 2m high tomato plant with its two tomatoes.

Last week I held a short live presentation at UNIS about my internship, but since most of you probably were not able to attend, I will outline here what I talked about.

Polar permaculture is an ambitious and challenging project. To overcome the difficulties of the climatic conditions so far north, a good team of engaged volunteers and students is essential. Everybody brings in different skills, ranging from scientific background to practical skills, as well as new ideas. I am very happy to say that our team works very well together, we can rely on one another and know everyone will do their part.

Looking back, I really enjoyed the practical aspect of the work, especially when I was able to be creative and contribute something useful. ‘Hands-on’ definitely was a nice way to complement the normally more desk-based studying at university. Also, progress felt less ‘abstract’, other than an essay that will only ever be seen by the marker, the products of my work at Polar Permaculture were seen – and even eaten – by others.

Comparing student culture and employee culture I believe this cannot be generalised. Other internships or work in other businesses could be very different and be influenced by many factors. As I pointed out in my presentation, my internship felt more like being part of a family business where every member of the small team can shape the development of the business equally.

My biological knowledge was of limited use because my first two years at university were focused on animal biology, however, practical experiences of growing herbs and vegetables on our small farm at home in the Orkney Islands came in handy. I could have drawn from my biological background more, if animals had been part of the growing cycle, for example by utilising manure to improve compost quality but unfortunately Svalbard legislation does not allow this.

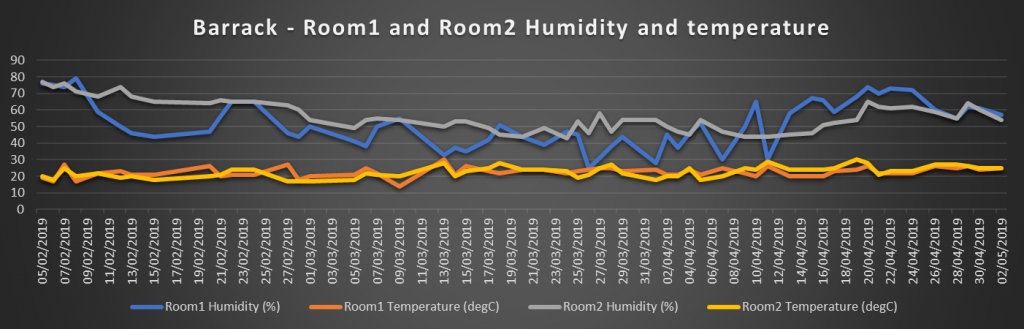

On the other hand I gained valuable experience, often simply through learning-by-doing or even ‘trial and error’, in gauging environmental conditions for different plants and figuring out what specific needs they had regarding nutrition, water, temperature, light requirements and humidity.

Currently I am studying Sustainable Development and given the present debate about agricultural production and food miles in the context of climate change, I will certainly look deeper into options for local and sustainable food production, even under such difficult conditions as in Svalbard.

And I will certainly set up some experiments back home in Orkney, where harsh conditions make growing food similarly tricky and there is a lack of locally produced products.